Sinai & Gaza - Part 1: pre World War I

Edmund Hall (ESC 239)

Over the last 20 years or so I have attempted to collect material relating to Gaza and the Sinai. This was born out of an interest in military history, particularly ancient and twentieth century. I naively thought that as the wars of 1948 to 1973 were recent events philatelic material would be plentiful, easily found and above all cheap.

While attempting to acquire material I have squirreled away various articles and notes with the intention of writing a series of articles, breaking up the various aspects of the combined philatelic information into historical sections. This is the first, covering the period up to the start of the First World War. I say Sinai and Gaza, but have used this as quite a loose definition, taking my cue from the Red Queen: “It means anything I say it means, and leaves out anything I say it’s not”. For instance, I have not included Kantara in the Sinai, while others do, as I have assume that the post office is on the west side of the Suez Canal and so in Egypt proper. By this measure, then, should Kantara Sharq (Kantara East) be included?

Gaza probably gets its name from the Semitic root for fortified town (castle). The meaning of Sinai is uncertain. The peninsular, or parts of it, is referred to in the Bible as Sinai, Sin, Tsin, Shur, Pharan and Choreb.

The name Sin (and hence ultimately Sinai) possible originates with the early Mesopotamian Semites, originating in Ur, who worshipped the moon god Sin. After their conquest of Syria, Palestine and Elam, which was considered to have been due to the favours of the moon god, they named the extremity of their new empire after Sin in gratitude.

Shur comes from the Egyptian for wall, as Sinai was considered a defensive wall against barbarian invaders from the East. This was deemed virtually the only importance in this otherwise seemingly worthless piece of land. But as the concept of defensive barrier applied only to the northern part, the interior of Sinai was, until the twentieth century, essentially ignored from the point of view of ownership and control. The idea of Sinai as defensive territory lingers on today, although only a cursory look at its history indicates the fallacy of this argument. It has been no barrier over the course of time to some 50 invading armies including Ancient Egyptians, Assyrians, Hittites, Babylonians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Franks, Ottomans, French (Napoleon), British and lately Israelis.

One question that arises is how do Sinai and Gaza relate to Egyptian philately? Other then the Egyptian occupation of what has been come to be known as the Gaza Strip, I think there is little argument to include Gaza. But what then of the Sinai? Some may even think this an odd question, as the Sinai now constitutes two of the provinces of present-day Egypt and warrants its own chapter in Peter Smith’s book. I ask it because from the collecting point of view I find more Holy Land collectors express an interest in the Sinai then do Egyptian collectors. I also have heard the view, from more then one collector, that it is more part of the Holy Land then of Egypt. The important point here, of course, is that if it is not Egypt, then some of my material is Egypt used abroad. If it is Egypt, then material not emanating from an Egyptian post office is Foreign Post in Egypt. In either case, doesn’t this mean the value of my collection must be seriously increased!

Did Sinai belong to Egypt, Palestine or Arabia, or was it an entity in itself? To all these one should, perhaps, add the status of Sinai from the standpoint of international law, but that is beyond the scope of this study. Morphologically, Northern Sinai is a stepping-stone, a link, between Asia and Africa, of both of which it is a continuation. There is no distinct natural line dividing either the Negev and Sinai or the Isthmus and the eastern part of the Delta (unless the Suez Canal be regarded as such). Southern Sinai, on the other hand, though geologically a continuation of both the Arabian Peninsula and the eastern portion of Africa, is morphologically separated from both by the two arms of the Red Sea: the Gulf of Suez and the Gulf of Eilat.

As far back as the first dynasties, in the third millennium BC, the Egyptian pharaohs aspired to exploit Sinai minerals, and exercise political control over Palestine and southern Syria. Though later their endeavours were often successful, Sinai was never considered an integral part of Egypt. Hans Goedicke has recently shown that even the incorporation into Egypt of the eastern Delta was a gradual process, completed only during the time of the 6th Dynasty (last quarter of third millennium BC), and consolidated at the time of the 12th Dynasty (first quarter of the second millennium BC). During the latter, the period of the Middle Kingdom, political control over Sinai was finally established. Nevertheless, the eastern borderline of Egypt was well defined and defended by “The Wall of the Ruler” - mentioned in contemporary Egyptian literary documents (The Tale of Sinuhe; The Prophecy of Nefer-Rohu, Papyrus Leningrad 116A) and archaeologically confirmed for the period of the New Kingdom by a line of fortifications running more or less parallel to the present-day Suez Canal (e.g., Sila = Tell Abu Seife, 3 km east of modern Kantara, which served as a frontier post; Tkw = Tell Maskhuta, in the east of Wadi Tumilat, west of modern Ismailia). This wall is alluded to in the biblical geographical term shur (=wall) - Genesis 20,1; 25,18; Exodus 15,22; 1 Samuel 15,7; 27,8.

On the other side of the peninsula, the territories of Canaan, and thereafter Judah and Israel, never included Sinai, for their southern limit was “the river of Egypt” (Numbers 34,4-5; Joshua 15,4; 47; 1 Kings 8.65), also mentioned in Assyrian documents of the eighth century BC. This, in spite of its name, was not considered part of Egypt; according to biblical concepts, Egypt began at the Pelusiac branch of the Nile shihor (Joshua 13,8; 1 Chronicles 13,5).

In the Middle Kingdom, Sesostris 1 established Egyptian sovereignty in Sinai, demonstrating his achievement by founding a temple at Serabit el Khadem. Nevertheless Sinai was still considered the land of the Asiatics, the “Sand Dwellers”, the semi-nomadic Shasu. In the New Kingdom, beginning with Tuthmosis III (middle of the second millennium BC), northern Sinai was continuously under Egyptian power and administration. “The Way of Horus” was fortified and kept well supplied. Yet even in this period, Sinai was not included in the concept of Egypt proper, and the capital city Per-Ramesses - the Delta residence of the 19th Dynasty - is still described as “the forefront of every foreign land, the end of Egypt” [Papyrus Anastasi 111,9; cf. Papyrus Anastasi IV,6, where Ramesses is described as being between Djahy (Palestine ) and Ta-mery (Egypt)].

With the decline of Egypt’s power in the 20th Dynasty (towards the end of the second millennium BC) she made no further claim to Sinai, which once again became no-man’s-land. But in their struggle for domination, Egyptian, Assyrian and Persian armies traversed Sinai back and forth, with demarcation lines constantly shifting (Herodotus Book 111,5: “they are Syrian as far as the Serbonian marsh ... from this Serbonian marsh, where Typho it is said was hidden, the country is Egypt.”).

The victories of Alexander the Great put an end to the Persian Empire and united the whole Near East - including Palestine, Sinai and Egypt - under his rule. It was only during the incessant wars among his successors that a border between Syria and Egypt, west of Rafiah, was established. The short-lived Hasmonean kingdom of Alexander Jannaeus extended west beyond this line and included El Arish, but when Pompey (63BC) established Roman supremacy he annexed all the coastal cities east of El Arish to Syria.

In the Hellenistic and Roman periods the border seems to have been between El Arish and Rafiah, which was considered the first city of Syria. During the Roman and Byzantine era the Sinai grew in military commercial importance, with the Romans building military posts every 22km (14 miles), the length of one day’s march of a Roman legion. The exact frontier kept changing its location: in the Hellenistic and again in the Byzantine period it was Bitylon, whereas in the Roman period it was Bethaffu. From there it made a sharp bend south, toward Suez. The coastline, including El Arish (then called Rhinokolura), Osracina and Mons Casius, belonged to Egypt, whereas the remainder, the bulk of central and southern Sinai, was part of Palestina Tertia. In the Byzantine period, this civil administration had its counterpart in the church administration (the Council of Nicea, AD325).

The Arab occupation of the Near East did not basically change the Byzantine administration and the division of provinces remained almost the same as before. There are minor differences of opinion among Arab medieval geographers as to where exactly Palestine ends and Egypt begins - some mention El Arish as being near (not within) Egypt; others include the entire coast of Sinai within Egypt. When Amr ibn al Aas set out in 639 with a band of 3,500 to conquer Egypt, by way of Gaza, at Rafiah he received post haste a dispatch from Umar ibn al Khattab, leader of the Muslims (caliph). According to tradition, Amr ibn al Aas suspected the purport of this despatch, and did not open it until the next day, when he had reached Al Arish. When he did so, he found that the caliph had ordered him, if he received the letter while he was still in Palestine, to abandon the operation. If, however, the despatch reached him when he was already in Egypt, he was to proceed. He then enquired innocently from those standing near, whether he was in Egypt or in Palestine. When they replied that they were in Egypt, he ordered the continuation of the march. This letter could possible claim be the most important piece of postal history in the history of Egypt. But like the Byzantine concept of Palestina Tertia, the Tih plateau (=central Sinai) is regarded as belonging to the Negev.

From the end of the 13th century, during Mameluke as well as Ottoman rule, Egypt, Sinai and Palestine again constituted part of one empire, borders being of minor importance. Administratively, the status of Sinai was not clearly defined; parts were sometimes attached to the province of Damascus or Gaza, sometimes to the Hedjaz or Egypt. It never became a sanjak (province) in itself, always being part of two administrative divisions. The Ottomans built new forts at El Arish and Nakhl, the latter a stepping-stone to Aqaba and the conquest of Hedjaz.

Things started to change with Napoleon’s expedition to Egypt in 1798-99, when European interests began to influence Near Eastern politics, and with the awakening of nationalism.

Egypt was a province of the Ottoman Empire at the beginning of the nineteenth century, when Mohammad Ali seized power (1805-1811) and was appointed by the Sultan as Pasha of that province. In 1830 he rebelled against his Turkish overlords, his son Ibrahim Pasha invading Palestine (October 1831) and adding all the provinces as far north as the gulf of Alexandretta (the frontier of present-day Turkey) to the territories ruled by his father.

In 1839 the European Great Powers, fearing the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, decided to intervene in the Turco-Egyptian conflict and called a conference in London. Mohammad Ali agreed to withdraw from all the territories he had occupied and to accept the authority of the Sultan in exchange for the hereditary government of Egypt. The Treaty of London (July 15, 1840) contained a demarcation of “Southern Syria”, which included Sinai in that province. The Sultan granted Mohammad Ali a firman in February 1841 in which he promised him succession to “the government of Egypt within its ancient boundaries, such as they are to be found in the map which is sent unto thee by my Grand Vizier”. This included a line drawn from east of El Arish to Suez as the boundary of Egypt. Of the two maps defining the exact boundary, however, one was lost in an Egyptian fire. In 1906 the Turks still claimed to be in possession of the other map, but its existence was considered doubtful.

Turkey remained the suzerain power, it being laid down that each hereditary governor of Egypt upon his succession must obtain a firman of investiture from the Sultan. This definitive statement of the Ottoman Government on the subject declared explicitly that Sinai was not part of Egypt. All the firmans of investiture granted to Mohammad Ali and his successors contained a reference to the territory in respect of which the grant was being made, but none of them included Sinai either specifically or inferentially.

As a result of British pressure, Turkey also granted Mohammad Ali permission to man a small police post at Nakhl (Central Sinai) and to control the “pilgrims’ road to Mecca” including Aqaba and portions of the west coast of the Arabian Peninsula. There was therefore a certain measure of Egyptian control over parts of Sinai, which were not included in its official boundaries, but two factors must be borne in mind: there was no Egyptian administration in Sinai in the 19th century; and the entire matter was of no significance, since all these territories were parts of one and the same Ottoman Empire.

Sinai, in the first half of the 19th century, was of little importance to either Egypt or Turkey; but this changed radically with the opening of the Suez Canal (1869), and even more significantly when Britain purchased the shares of the Canal Company (1875) and then, after the Arabi revolt, occupied Egypt (1882). It now became an important aim of British policy to shift the boundary as far as possible away from the Canal. On the other hand, Turkey took a more active interest in Sinai in connection with plans for the Suez and Hedjaz railway. In the clash between Great Britain and Turkey, the weaker side, Turkey, had to give way, regardless of legalities.

The conflict came to a head in 1892. In that year the Ottoman Government granted a firman of investiture to the new Khedive, a title first granted to Mohammad Ali’s grandson Ismail Abbas Hilmi, which contained a more specific definition of Egypt’s boundaries (referring to the firmans of 1841 and 1865): Aqaba was removed from Egyptian control and annexed to the Hedjaz. The reason given by Turkey was that the pilgrims from North Africa had long ago ceased to use the overland route, preferring the sea route, whereas the pilgrims from Syria still made use of Aqaba. The British, who understood this firman to determine the Egyptian frontiers from Suez to El Arish, delayed its promulgation.

On April 8, 1892, as a result of the intervention of the British Consul-General and virtual ruler of Egypt, Sir Evelyn Baring (soon to become Lord Cromer), and the pressure brought to bear on Turkey, the Grand Vizier sent an explanatory telegram confirming Egypt’s right to administer “Mount Sinai”, provided that the garrison towns along the Hedjaz route reverted to Turkey. This telegram was the first Ottoman document to grant Egypt authority in Sinai, but it was phrased in vague terms and did not specify any boundaries. There are discrepancies in the text: police stations and positions placed in Sinai for a specific purpose does not amount to administration.

In spite of this, the British Consul-General informed the Egyptian Foreign Minister that the telegram was to be interpreted as drawing the boundary of Sinai under Egyptian authority from east of El Arish to Aqaba. Turkey neither confirmed nor denied this.

Ten years later, on September 8, 1902, the Sultan confirmed the status quo in Sinai. Then, when in 1905 the Hedjaz railway reached Ma’an, only 125 km from the Red Sea, the importance of Aqaba was suddenly enhanced. Turkey intended to use the railway, with its branch line to Aqaba, as an alternative to the Suez Canal and therefore established a military presence at Aqaba, as well as at Taba, 10 km. to the south.

To this day, certain points in the ensuing events have not been clarified: (a) Who was the initiator of activities: Turkey or Britain? (b) To what extent was Germany involved? Matters are further complicated by the fact that in the 1906 dispute the Muslim population of Egypt often sided with Islamic Turkey against the Anglo-Egyptian government. Ironically, perhaps, this was the opening of a new epoch in the history of modern Egypt: the awakening of nationalism. But at the time, it was just those nationalistic elements in Egypt who rigorously opposed the annexation of Sinai. When Lord Cromer pressed the Khedive, Abbas Pasha, to claim southern Sinai for Egypt, he refused to do so on the grounds that it was not within the boundaries of his country.

On January 10, 1906, a British officer, W.E. Jennings-Bramley (often known as Bramley Bey), commanding a small Egyptian force of five guards, pitched his tents at Umm-Rashrash (modern-day Eilat) and declared his intention of constructing a police post there and others all along the Aqaba-Gaza road. The Turkish Governor of Aqaba, Rushdi, claimed this to be trespassing. Bramley was forced to return to Nakhl, and the Turks immediately set up a police post at Umm-Rashrash (January 12,1906).

The second episode in the drama occurred ten days later, when a small Egyptian coastguard vessel. the Nur-el-Bahr, with a British captain, anchored at Coral Island and its men made an attempt to land at Taba. Turkish troops occupying Taba prevented the landing. Bramley arrived on the scene, but could not change the situation, though on the way he managed to put up a post at Ras el-Naqeb, whereupon Rushdi stationed a few Turkish soldiers at the same place. In February the Turks increased the number of their troops in Aqaba and the British dispatched their battleship Diana to the Gulf of Eilat. During the next two months the Turks defied repeated British demands to evacuate Taba. At the end of April the other side of Sinai, Rafiah, flared up and Lord Cromer sent a battleship to the Mediterranean shore of Sinai as well.

In the meantime, an attempt was being made in Cairo to settle the issue by way of diplomatic negotiations. The British Government protested against the Turkish occupation of Taba, declaring that it belonged to Egypt. Mukhtar Pasha, the Turkish delegate at these talks, on the other hand, claimed that the boundary line El Arish/Aqaba was in fact El Arish/Suez /Aqaba, i.e., dividing Sinai into three triangles, two of which were administered by Egypt, the third, including Taba, by Turkey herself. The British had to admit that this was the way the line was drawn in most maps. Mukhtar Pasha considered this triangle essential for the continuation of the Hedjaz railway as far as Suez, but was willing to compromise by bisecting Sinai along the line El Arish/Ras Mohammad.

His argument was that administration of Sinai had been entrusted to the Khedive exclusively for the purpose of protecting the pilgrims’ route to Mecca, and that when in 1892 Aqaba had been restored to Turkey, the eastern coast of Sinai, as far as Ras Mohammad, had similarly reverted to direct Ottoman rule, leaving only the western half of the Sinai peninsula under Egyptian administration. This proposition was rejected out of hand by the British, who concentrated troops and naval forces in Egypt as well as the Eastern Mediterranean, turning the local border clash into an international threat of war.

On May 3 the British Government presented the Sultan with an ultimatum, demanding that he evacuate Taba within ten days and accept the Turco-Egyptian boundary as running straight from Rafiah to Aqaba. It is of interest to note that, while the British insisted that the boundary had always been at Rafiah, Rafiah had never before been mentioned in this dispute. All Turkish attempts to settle matters without complying fully with the terms of the ultimatum were fruitless and on May 14, threatened by the Royal Navy and intimidated by France as well as Russia, Turkey was compelled to accept the British terms.

When the joint Turco-Egyptian commission preparing the map found themselves disagreeing, Turkey had to give way once more to British pressure. Though the oases of Kuntilla, Ein Qdeis and Qseima along the Gaza/Aqaba road should, according to a straight line drawn from Rafiah to Taba, have been on the Turkish side of the line, they were included on the Egyptian side because Britain threatened that otherwise she would insist on including the Arava valley and Aqaba in Egypt as well. The agreement was signed on January 1, 1907, with the line drawn from Rafiah to Taba. Turkey’s only achievement was the retention of Umm-Rashrash, as a defence for Aqaba.

There are therefore basic differences between the Rafiah-to-Taba border and all the other borders of Palestine. (a) It is earlier, fixed in 1906, whereas the other lines were negotiated only after World War I. (b) It was originally not an international border, but an administrative demarcation line, a division within the Turkish Empire. (c) This legal status was never changed or discussed by any international forum. When, in 1922 Britain was granted a mandate over Palestine, this line was automatically taken over, and at the end of the Arab-Israel war in 1949 was accepted as the ceasefire line by both Egypt and Israel. After World War I there was a notable failure to define the status of Sinai. As early as 1914, Britain declared Sinai to be a “protectorate”, while Egypt continued to act as administrator, but without ever formally annexing the area to the Egyptian kingdom established in 1922. Under the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923 Turkey gave up its colonies, but southern Sinai was not included in the list.

While the debate concerning the future of the Sinai and Palestine crackled, the British judiciously decided to hold on to the peninsula as a separate province, in truth a part neither of Egypt nor of the Palestine Mandate (the territory granted to England by the League of Nations). It was administered under an organisation called the Occupied Enemies Territory Administration, with Lieutenant Colonel Alfred Parker as governor until 1923 and his deputy, Major Claude Jarvis, taking over the command from 1923 to 1936. The governor of Sinai was responsible for law enforcement, taxes, public works, public health, agriculture, and education of the native population, at that time about 30,000 Bedouins and 10,000 in El Arish. These functions of government were administered by a body of about 300 officials, including a Sudanese Camel Corps, which watched over four administrative districts (Northern, Central, Southern, and Kantara), each under a mamour, or district inspector. A prison and hospital were established at El Arish, with clinics in six other locations.

The British plan in the Sinai was to maintain the status quo until some permanent solution could be found for the troublesome peninsula. It wasn’t easy. The Bedouins, in particular, were restive because during the anarchy of war they had become entranced with what to them was the ideal human condition of mafish hakuma, “no government,” and they could pretty much run things their own way, for a change. It is worth noting that the railway across northern Sinai was entrusted to Palestine Railways after WWI with the line ownership being retained by the British Army. The Kantara-Rafiah line was finally handed over to the Egyptian state railway on April 1, 1948.

Meanwhile, Egypt exerted more and more control over its own destiny. Nationalistic unrest compelled the British to relinquish most of their hegemony over the seething protectorate, leaving them finally with little more than a military presence in the Suez Canal area. Sultan Ahmed Fuad Pasha proclaimed himself king, being succeeded by his son, Farouk, and Egyptian influence spilled over into the Sinai.

But then the Second World War turned things around and made the area militarily significant once again. The British Army occupation swelled for the second time in 25 years. Most of the action was, of course, in the Western Desert of Egypt, holding back the Axis forces at El Alamein, so the Sinai was spared another round of war’s ravages, reverting to its role as strategic buffer and logistics base. With the end of the war, however, the complexion of the entire Levant changed radically. The old, tired colonial powers gave up one by one their Middle Eastern possessions; and Egypt, the most populous, most modern, most dynamic of all the Arab states, took undisputed control of the Sinai, with the blessing of the British, right up to the Palestine border.

On May 14, 1948, after the United Nations General Assembly had endorsed a partition plan for Jewish and Arab states in Palestine (with Jerusalem designated as a separate entity), war-weary Britain had decided to throw up its hands and end its Palestine Mandate, the State of Israel was declared. Israel was almost immediately at war from all sides, with Egypt sending her army through the Sinai to occupy the Gaza Strip and put pressure on the Israeli settlements in the Negev. After a short UN-arranged truce, the Israelis took the offensive, and by January 1949 they had driven the British-equipped and advised Egyptian Army out of the Bir Asluj-Auja El Hafir area on the Negev-Sinai frontier and were poised to take Rafiah, El Arish, and the Gaza Strip from the Egyptians.

The great powers, alarmed at this totally unexpected turn of events, put heavy pressure on Israel to withdraw its forces from the Sinai. Israel complied, stating for the record that it didn’t covet any Egyptian territory. In February 1949 Egypt signed an armistice agreement with Israel in which Egypt retained the Gaza Strip and all of the Sinai. The Sinai had become recognised, by the parties involved, as an integral part of Egypt with the 1906 border from Rafiah to Taba as the demarcation between Sinai and the Negev.

The anomalous position of Sinai as a territory that locally had never been part of Egypt was brought to the attention of the British Parliament in December 1956, following the Sinai Campaign. While, therefore, Egypt has long had a recognised right to administer the Sinai Peninsula, she has never acquired sovereignty over the area. There has been no de jure recognition of the annexation of Sinai to Egypt. However this was not pursued. and Israel withdrew her forces form Sinai according to the 1906 Rafiah-Taba line.

An outcome of the 1967 war was again the Israeli occupation to the whole of the Sinai. In 1982, consistent with UN Resolution 242 and the 1978 Camp David Accords, Israel withdrew from almost all of the peninsula which it had occupied, but refused to cede to Egypt the Taba Strip, a small parcel of land along the Gulf of Aqaba. The strip was the site of a 326-room resort hotel, popular with Israeli tourists, built by an Israeli entrepreneur in the early 1980s for $20 million. Israel claimed sovereignty over Taba, citing as justification the 1906 British boundary maps showing the land to be part of Turkish-controlled Palestine rather than British-controlled Egypt. Egypt disputed Israel’s claim, citing as justification the actual 1917 border demarcations (which put the Taba Strip in Egyptian hands), pre-1967 sovereignty over the strip, and the return of the strip to Egypt after the 1956 Arab-Israeli war.

Two years later, the arbiters (French, Swiss and Swedish international lawyers plus one representative from each disputant country) ruled in favour of Egypt. Final negotiations were settled on February 27, 1989, when Israel and Egypt signed an agreement that turned over the Taba Strip to Egypt. Egypt purchased the Aviya Sonesta hotel resort for $38 million and took possession of Taba on March 15, 1989.

It would seem, then, that El Arish has for the last few centuries been considered by most as part of Egypt, so from the opening of the first Egyptian post office in 1883 to the present we can fairly safely say it belongs to Egyptian philately. With Tor one can possible take a slightly different view, that until the drawing of the Rafiah/Taba line in 1906 few writers would have considered it Egypt as such. The Sinai was treated as an entirety in its own right, being nominally part of the Ottoman Empire - so from the opening of the Tor post office in 1889 until 1906 others may claim it as part of their philatelic sphere.

The Sinai was of course the main postal route between Egypt and Asia and the empires of Syria, Mesopotamia and Anatolia. To read the accounts in the book published by the Egyptian Postal Administration in 1934 and others published in L’Orient Philatélique and elsewhere about the posts of the Arab empires one can get the impression these were being invented for the first time. This is in fact not the case: it is quite amazing to see how people have dealt with the problems of long-distance communication throughout history. References to telegraphic/post systems can be found in almost every period from which written records survive. The ancient empires from Sumer onwards depended for their very existence on some form of message conveying system. The fact that the new empires as they arose seemed to inaugurate a new relay and/or pigeon service was simply either to repair those destroyed in the wars of conquest or where the preceding system, organised by a decaying and now defeated empire, had fallen into disrepair.

The Sinai was for most of its history part of some form of organised postal system, especially when the eastern shores of the Mediterranean and the Nile Delta were part of the same empire - starting with the Egyptian empire of Sesostris I, who reigned from 1971BCE to 1928BCE, and lasting right through to the British Empire ending in 1948. Nearly all forms for the conveyance of messages have been used during this time, including runners, donkeys, camels, horses and of course pigeons. The pigeon posts in the Sinai cover nearly 2,500 years from earliest times up to the last attempt between the two world wars. Other methods include smoke signals (beacon fires), flags and polished metal.

The earliest mention of domesticated pigeons comes from the civilisation of Sumer, in southern Iraq, from around 2000BCE. Most probably it was the Sumerians who discovered that a pigeon or dove will unerringly return to its nest and started the first pigeon posts. King Sargon of Akkad, who lived ca. 2350BCE in Mesopotamia, had each of his messengers carry a homing pigeon. If the messenger was attacked en route, he released the pigeon. Its return to the palace was taken as a warning that the original message had been lost, and that a new messenger should be sent. The blue rock dove, Columba livia, originates from this part of the world and is the ancestor of today’s racing pigeon. By the twelfth century BCE pigeons were being used by the Egyptians to deliver military communications and it was in the Near East that the art of pigeon rearing and training was developed to a peak of perfection by the Arabs during the Middle Ages. A pigeon can fly 60-100km/hr over distances of 800km or more.

Ancient Egypt, of course, had a post system in the delta and an early document (ca. 2000BCE) sent by a scribe to his son emphasises the importance of writing and the bright future of a scribe in government employ. In the reign of Tuthmosis IV (1401-1391BCE) relations between Egypt and Sumer changed from conflict to peaceful alliance which lasted for at least 40 years The period is documented in the diplomatic correspondence of Amenophis III (1391-1353BCE) and Amenophis IV (1353-1335BCE) of Egypt. Three hundred and fifty letters written in Babylonian cuneiform on clay tablets have been found at Tell el-Amarna, the capital of Amenophis IV, the heretic pharaoh better known as Akhenaten.

Many of the letters concern the government of Palestine and the Levant. Gaza then had an Egyptian governor, with some Egyptian garrisons up to Jaffa. Letters from these rulers and governors include professions of loyalty, requests for assistance and accusations against neighbouring city rulers. The Amarna letters also record diplomatic exchanges with the rulers of independent countries including Mittani, Hatti, Arzawa in the west of Asia Minor, Alashiya (Cyprus), Assyria and Babylon. These rulers treated with the pharaoh on equal terms, addressing him as their “brother”, whereas a vassal ruler used language such as “the king, my lord, my sun god, I prostrate myself at the feet of my lord, my sun god, seven times and seven times”.

Compared with today’s text messaging, one can have sympathy with the lament “... the art of letter writing isn’t what it used to be ...”. I particularly like a letter from Tushratta, having given away his daughter Tatu-Hepa in marriage, suggest that the pharaoh might send him a statue of her cast in gold so that he would not miss her!

By the thirteenth century messenger services must have become quite routine. In a fragment of the log kept by an Egyptian guard during the reign of King Merneptah (successor of Ramses II), from 1237BCE to 1225BCE, we find a record of all special messengers seen at a guardpost on the Palestinian border with Syria: at least once or twice a day a messenger would pass through with either military or diplomatic missives. So the Sinai, for most of this period, probably had fortified post houses, most likely based on the wells, to support the mail service.

Egypt was conquered by the Assyrian king Esarhaddon in 671BCE and then by Cambyses of Persia in 512BCE. The Assyrian, Babylonian and Persian kingdoms all supported post routes as an essential method of maintaining control. That knowledge is power is not a new concept.

We read in the Babylonian archives, found in Boghazkhöi, complaints about attacks by Bedouins on royal couriers. The early Babylonian kings placed royal guards at regular distances along the roads. They were originally intended only for the protection of travellers, but their presence led quite naturally to a number of major improvements in the messenger system. The first was the establishment of a relay system, where a message was passed from guard station to guard station, each time carried by a new runner. The second decision was to equip the guard posts with beacons, so that simple alarm or warning signs could be passed quickly from one end of the road to the other, without the need for a human runner. Every bêru [an Assyrian distance unit, corresponding to a two-hour journey] a beacon was set up. It can be assumed that the beacons referred to were not quickly improvised for the occasion, but were part of a permanent network of roads and guard posts. The Biblical book of Jeremiah, from ca. 588BCE, also contains a clear reference to the relay system

King Cyrus the Great, who lived from 599 to 530BCE and ruled Persia for the last 19 years of his life, was credited with improvements to the courier system. Xenophon (430-355BCE), writing more than a century later, described it in Cyropaedia, his biography of Cyrus, as follows:

“… we have observed still another device of Cyrus for coping with the magnitude of his empire; by means of this institution he would speedily discover the condition of affairs, no matter how far distant they might be from him: he experimented to find out how great a distance a horse could cover in a day when ridden hard, but so as not to break down, and then he erected post-stations at just such distances and equipped them with horses, and men to take care of them; at each one of the stations he had the proper official appointed to receive the letters that were delivered and to forward them on, to take in the exhausted horses and riders and send on fresh ones. They say, moreover, that sometimes this express does not stop all night, but the night-messengers succeed the day messengers in relays, and when this is the case, this express, some say, gets over the ground faster than the cranes.”

The system lasted. In his History, Herodotus describes with admiration how the relay system functioned at the time that Xerxes ruled Persia, between 486 and 465BCE:

“This is how the Persians arranged it: they saw that for as many days as the whole journey consists in, that many horses and men are stationed at intervals of a day’s journey, one horse and one man assigned to each day. And him neither snow nor rain nor heat nor night holds back for the accomplishment of the course that has been assigned to him, as quickly as he may. The first that runs hands on what he has been given to the second, and the second to the third, and from there what is transmitted passes clean through, from hand to hand, to its end.”

The phrase “neither snow nor rain nor heat nor night …” is used in a slightly different, and not too literal, translation for an inscription over the width of the main US Post Office in Manhattan. It reads “neither snow nor rain nor heat nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds”. The Persian couriers, of course, did not walk rounds but ran a relay system.

The Persian Empire gave way to the Ptolemaic and then the Roman, whose postal system was called the cursus publicus. As previously mentioned, the Romans had posts dotted across the Sinai as part of their post roads. Originally, they used human runners to transport the messages. Later, when the system became larger, they switched to couriers on horseback, as in the Persian system. Each of the Roman relay stations kept a reserve of not fewer than 40 horses and riders. The speed of the Roman relay system was approximately 80km (50 miles) per day for regular mail, and double that for express mail, although these numbers might be based on human runners rather than riders on horseback. In an attempt to curb abuse, messengers, called strators, were issued special licenses from the Roman emperor that qualified them for the free exchange of horses at relay stations.

Over the years, responsibility for the upkeep of relay stations became a hot political issue. Roman rulers alternately strived either to delegate the responsibility to local communities, in order to reduce the tax burden on the state, or to transfer the responsibility back to the state, in order to secure more consistent maintenance. In the end, neither the state nor the local municipality was willing to continue covering the expenses, and the system perished. Perhaps a familiar tale that many today will recognise.

Although mention is made of the Byzantine horse posts along the Nile I can find little mention of postal systems for Egypt and the Sinai during the latter part of the Roman period, and with Byzantium becoming the new Roman capital in 315 it would make sense that the only meaningful communications route would be by sea - Alexandria to Byzantium. No references to postal routes across the Sinai are found in the brief Persian incursion in Egypt in 616 or from the Arab invasions in 636. It seems highly likely, therefore, that the Roman postal stations across north Sinai had fallen into disuse and had to await the Arab empires for their reintroduction.

There was not a single Arab postal system, as these came and went with the dynasties and with the changing fortunes within those dynasties. This factor gives rise to the multiple claims of the “first” pigeon posts from the various Arab caliphs ether in Baghdad or Cairo.

The caliphs who ruled the early Muslim Empire, AD onwards, inherited the Byzantine postal services along with their bureaucracy, which would include the Byzantine beredararioi organisation of official government messengers of Egypt. In Arabic, as barid (post), the term itself is therefore possibly of Persian origin. The first Umayyad caliph of Baghdad, Mu’awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, 661, is said to have been the first to reintroduce (or, more likely, improve) a general postal system during Islamic rule.

The pigeon post developed into a regular airmail system in the service of the state. The postmaster general had agents in every town, who collected and sent him all public information, which he in his turn reported to the caliph either at length or in an abridged form. With these eyes and ears of the government, and with the local postal centres stocked with well-trained pigeons, there was little chance of the caliphs failing to be warned of potential troublemakers in the provinces.

Even the overland mail routes ensured swift postal service. Deliveries between Cairo and Damascus normally took about a week. Riders changed horses at special stations which were located about 15 miles apart. This was called “express post”, with ordinary post being carried by camels through the same stops where there were government servants whose job was to prepare fresh animals for the next leg. At one time there were nearly a thousand postal stations in the Islamic Empire.

The local postmaster’s business was to inspect the various postmen appointed to his district, to report their number, their names and the cost of their maintenance, also to report the number of stations in his district, their distance from each other, and the names of the places traversed in the postal route. He was, moreover, bound to see that the mail-bags were duly transferred from one messenger to the other, and to arrange that each postman or courier started in sufficient time to reach the next station at the appointed hour.

It is recorded that Caliph El Mamoun, who died 833, felt so much pleasure in hearing news that in addition to the usual officers he kept a number of old women of Baghdad in his pay, in order that his court might be supplied regularly with all the town gossip. It seems pretty certain that the post under the caliphs did not leave or arrive at any stated time, but only when there were government despatches or noblemen’s letters to be forwarded. The letters of private individuals had to wait for one of these opportunities. Merchants had to make their own arrangements. In Arabia and Syria the letter carriers rode on camels; but in Persia letters were conveyed from station to station by running footmen, through in cases of emergency couriers where despatched on horseback.

The first recorded example of airmail parcel post in history makes an interesting tale: Aziz, the Fatamid caliph (975-976), had cherries grown in Baalbek, Lebanon, delivered to him in Cairo by 600 homing pigeons, each with a small silk bag containing a cherry attached to its leg.

Postal services were carried out by the tax collecting office and the person in change was called Al Dowidar or the “Prince of the Mail”. He had an assistant called Katib al-Sir, who distributed the mail personally. The postmen carried a brass badge about the size of one’s palm engraved on one side, “There is no god but Allah and Muhammad is His Prophet”. The other side has these words: “His Majesty the Sultan, King of the World, Sultan of Islam and Muslims, The Son of the Martyr Sultan.” This brass badge was attached to a scarf round the postman’s neck as a distinguishing badge.

Royal pigeons also had a distinguishing mark, and only the Sultan was allowed to touch them. If a pigeon arrived while he was eating he interrupted his meal, and if he was sleeping his retainers would wake him to receive the message. Nobody could touch a cable before he awoke. Training pigeons for postal work became a lucrative industry, as a pair of well-trained birds could bring up to a thousand gold pieces. These were thoroughbred pigeons, raised specifically to fly long journeys, and were given the special name of Hawadi, or “Express Pigeons”, by the Arab authors.

The cables carried by pigeon were written on a fine paper, especially prepared and styled “Paper for pigeons postal service”. Severe brevity was prescribed for the wording, even the preamble Bismillah (in the Name of God) being omitted. Only the date and hour were mentioned and the shortest expressions were used and unnecessary words omitted, in contrast to the accustomed flowery language. A special Arabic script called Ghubar was invented in the eighth century in part for the pigeon post. Minuscule in size, it became known as the Janah (wing) script and was considered the handwriting of conspiracy.

Ancient and modern writers give different distances between relay stations and speed of messengers and mean of transport. Distances of only 4.24km (2 2/3 miles) for horse posts and pigeon stations of 11km (7 miles) are reported in the 1934 Universal Postal Union Congress book, but I find this hard to believe and tend to favour other reports of 24 and 36 kilometres. This would be a day’s journey, though official najjab (couriers) went much faster, with distances of 150km (95miles) per day achieved. Besides horses, certainly camels and donkeys are reported as having been used, depending on the importance of the message or goods being carried. The pigeons themselves, for instance, are reported as having been carried by donkey to their release destination. The barid and its associated network of roads was considered second in importance only to the military in state expenditure.

Probably these postal arrangements operating across the Sinai were in operation to some degree through the Umayyad, Abbasid and Tulunid periods, as their empires always comprised as least Egypt and Palestine. It was not until the Seljuks conquered Syria and Palestine by 1079 that a definite disruption of the postal stations is recorded. The Seljuks deliberately destroyed the means of communication throughout Palestine in their war with the Fatamid Egyptian rulers and with the border between the two empires ending up similar to those of Egypt and Israel today there would have been no reason to maintain the post stations across the Sinai. Alp Arsalan, the Seljuk Sultan, in 1063 eliminated the Caliph’s posts and abolished the position of director of information and posts (Saheb al habar wal barid).

The Middle East soon after endured the Crusades and Egypt was not united with Syria until Nureddin, the Zanagid Sultan, took Egypt in 1169. He established a government mail service with many pigeon posts along the principal routes of his Empire, which may therefore have again included the Sinai, though I suspect not. The Turkish commander of Egypt was accompanied by his nephew Salah al-Din, who became ruler of Egypt in 1171 and gave rise to the Ayyubids. One can only suspect that some form of postal arrangement must have existed throughout this period, and reports suggest that irregular messengers (ressul) used racing camels. The Ayyubids gave way to the Bahri Mamelukes, and it was under the Mameluke Sultan al Zahir Baybars that the Arab postal system reached its peak.

When Baybars became Sultan of Egypt he organised, in 1260, a postal service on all the roads of his kingdom, so that mail from Cairo reached Damascus without hindrance. The service functioned regularly twice a week from Egypt to Syria up to the Euphrates and back.

In creating his service, Baybars used as his model the postal organisation (Ulak and Yam) of the Mongols, created by Ogodai (Okday) in 1234. Ulak is the Turkish term for post messenger and Yam is the Chinese definition of post-horse.

Baybars’ postal service was purely for governmental use, at the sole disposal of the head of the state, and the road was accordingly called the Sultan’s Road (Ed-Darb es-Sultani or Ed-Darb es-Sultan). The mail consignments received the name El Muhummatush Sherife i.e., “important matters of His Sublimity”. Baybars managed the postal directorate personally, just as he did all other governmental departments. The postal messengers who carried the mail to be forwarded were called Beridi and were selected from among the sovereign’s court-pages. The Beridi carried a leather letter-bag (Dsharab), and a yellow silk scarf with its end hanging over the back. Yellow was the emperor’s colour. The post messengers’ superintendent, the Mokadem ul-Beridye, controlled the sequence of the departing post messengers and provided their passage needs. At each post-station there were post-horse attendants (Sei’is) and post-horse drivers (Sawak).

In Damascus was stationed a manager of the postal service (Wali el-Berid) directly subordinate to the Sultan. Post-houses were placed on the post-road by tribes controlling each area, and they were paid accordingly.

Mail-routes under Baybars in 1260 included three main schedules in the Nile Delta, namely:

1. Cairo - Dumyat (Damietta)

2. Cairo - Iskenderiye (Alexandria)

3. Cairo - Iskenderiye through the desert parallel to route 2.

One route led across Gizeh, then along the Nile to the south.

Another route led cross Es Salahiye and Gaza into Syria.

Yet another route led across the Sinai peninsula, then via Medina and on to Mecca..

The postal service was maintained by camel riders. By the year 1273 the following post routes were established:

In 1261 From Damascus to Haleb (Aleppo)

In 1262 Haleb to El Bireh

In 1263 Gaza to Kerak

In 1264 Dimishk ush-Sham (Damascus) to Rahba

In 1266 Jenin to Safed

In 1268 Haleb to Baghras

In 1270 Homs to Masyaf.

In 1271 Homs to Crac (Kerak)

Horse centres (Merakis) were situated at intervals along the post routes. These sheltered essential personnel for the horses’ care. The riding post messengers exchanged their tired horse at each centre for rested, well-attended and well-fed mounts. In between these stations there were halts (Mavkif) where drinking water was made available for man and beast.

The 800km distance between Cairo and Damascus was usually covered in 8-10 days.

The pigeon-post, which was secondary to the horse-post, maintained stations in Alexandria, Damietta, Gaza, Kerak, Cairo, Jerusalem, Nablus, Deraa, Damascus, Baalbek, Hama, Aleppo, Bireh and Rahba.

The transmission of information by means of visual signals was of purely. military character. The remotest signal stations. Bireh and Rahba (Rutba), passed their signals to Damascus and Gaza by double affirmation as far as Damascus and by single affirmation from Damascus to Gaza. These messages were then forwarded by pigeon-post or horse post from Gaza to Cairo. The signals were made with the aid of smoke or fire, and transmitted in accordance with a certain code from the. top of elevated buildings, hills and the like.

These signal stations were installed along the horse mail-routes and came under the management of the horse-post; thus, the horse-post, pigeon-post and visual signals were united and co-ordinated in their service of forwarding information in the quickest way through the Mamelukes’ state from its remotest borders.

A note of Taqi ad-Din Ahmad al-Maqrizi (the Arab historian, 1364-1442) describes the colossal number of pigeon messengers put at the disposal of the sovereign for the despatch of his cables. He reports that in the year 1288 no fewer than 1,900 pigeons were in the stations of Cairo alone.

After the death of Baybars the network of post routes was enlarged between 1291 and 1347:

In 1291 - route from Damascus to Saida-Beyrouth-Latakia-Sahyun

In 1292 Haleb to Kal’at ar-Rum

In 1294 Kerak-Tripoli

In 1334 Kal’at Dshabir Ras Ayas-Haleb-Ain Tab-Bihisni-Darende-Bihisni Malatya-

Divrik-Kal’at ar-Rum-Kahta.

Through shortening the post-routes by adapting them to the commercial roads success was achieved in covering the distance between Cairo and Damascus in four days instead of eight and Cairo to Aleppo was reduced to five days.

When Timur the Mongol conquered Iraq in 1400, he tried to eradicate the pigeon post along with the rest of the Islamic communications network, as he realised its military importance, and by 1421 the postal system throughout Egypt and the Middle East had collapsed completely.

From 1517 to the French invasion Egypt was part of the Ottoman Empire and with successive famines and plague from the 14th century onwards it was much in decline: I can find no reports on the postal systems, if any existed. The Portuguese opening of the trade routes, round the Cape of Good Hope to the Far East, had made Egypt an unimportant backwater in world affairs.

The U.Heyd Ottoman Documents on Palestine (Oxford, 1960), dated November 18, 1577, gives an order to the Beglerbeg of Damascus:

“You have sent a letter and have reported that the chaush Mustafa who went to Egypt on government business had this time come to Damascus on his return journey and has related that on the roads from Damascus to Egypt there are no post-horses and the horses seized on the roads and in the districts from Gaza to Qatya do not get back to their owners until ten days later and many of them are lost...”

would appear to indicate that some sort of system was supposed to exist but did not seem to function, or at least not well. A further outbreak of plague in 1719 left the country impoverished and the French traveller Volney, visiting around 1784, described a depopulated country and Cairo as crumbling.

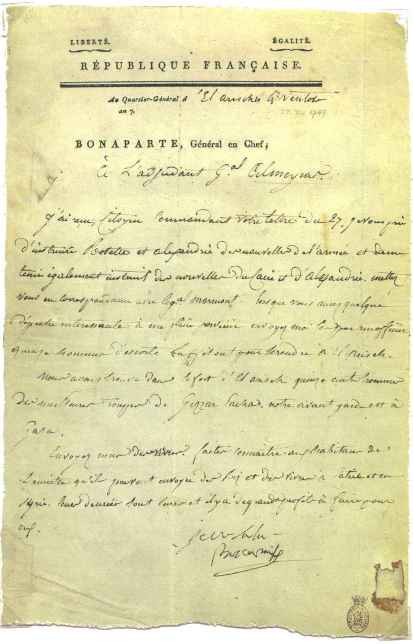

Napoleon invaded Egypt in 1798 and then attempted to march on Syria, but plague and other ailments decimated his troops and the expedition failed. The French postal system never included the Sinai but individual letters from Napoleon are known from this campaign, including one from El Arish.

After French and British invasions the Middle East was opened up to European travellers to the Holy Land and several collections of correspondence from the Sinai are known from those doing the Grand Tour. Typical of these is that of Charles James Monk, in 1848-1849, son of the Bishop of Gloucester and Bristol. Among the numbered letters (from “3” to “57”) and with date and place of posting neatly and conveniently written at the foot of the address panel of each, are letters from Alexandria, Cairo and the “Sinai Desert”. The letters, one assumes, were kept or forwarded by guides and posted at the main ports at a later date.

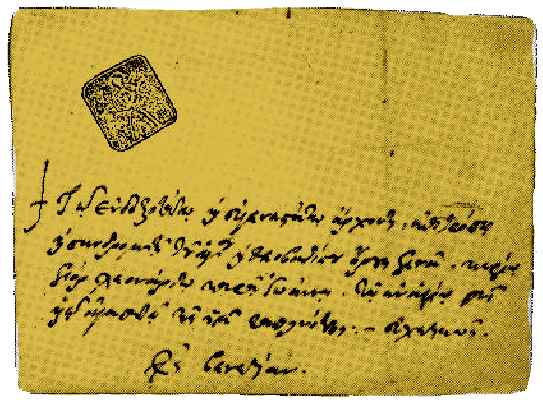

The other source of letters from the Sinai are those from St Catharine’s monastery, with handstamped markings from the monastery. Such a letter of 1751 is shown in Byam’s sale catalogue of 1961. It is described as probably the earliest stamp applied in Asia. I have seen a similar piece at the Israel 1999 exhibition, and I possess a postcard of 1912 with a cartouche in Greek. The apparently good strike in black, however, is on a matching background, preventing me from making any sense of it.

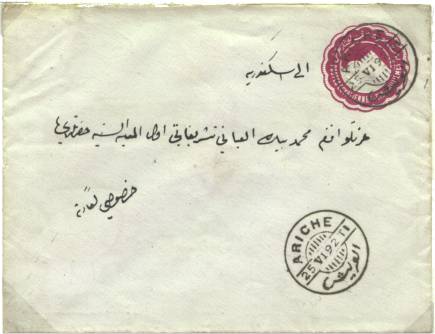

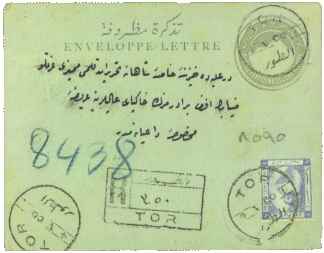

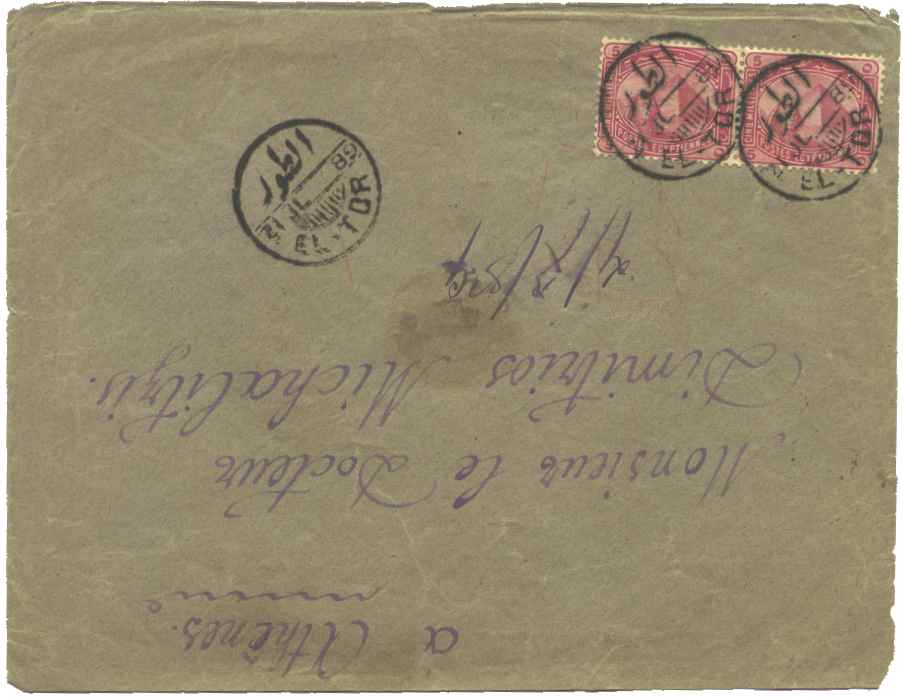

The first proper post offices in the Sinai were opened by the Egyptian postal services El Arish (Ariche) in 1883 and Jebel el Tor (Djebel-el-Tor) in 1889. These were the only offices to operate in the Sinai prior to the First World War, as they were the only places with any reasonable number of settled population. The office at Tor was operated as a quarantine station for the pilgrims returning from the Haj and the post office may have operated only during the quarantine periods. This could easily be checked by comparing the dates of use with the dates of the Haj, an exercise I have not attempted.

|

|

|

On November 2, 1914, Egypt was placed under martial law and a few weeks later was declared a British Protectorate, with war being officially declared by Britain on Turkey on November 5. At this time Egypt had only 5,000 British troops and it was estimated that the Turks could bring about 70,000 troops against the Sinai. Egypt immediately evacuated El Arish and Nekhl and the Turks crossed the frontier: by November 15 they had 5,000 infantry and 3,000 Arab auxiliaries in El Arish. Whether the handstamps were left, destroyed or taken back to Egypt I have no idea, but some time before November 15 the Egyptian post office at El Arish must have ceased to function. Tor was never taken by the Turks, although attempts to capture it were made, and as far as I can tell it continued to function throughout the First World War.

The postmarks as shown for El Arish and Tor are those I

have covering the period up to November 15, 1914.

The drawings have been taken

from publications, auction catalogues, photocopies and a few from my own

collection, either on cover or part strike on stamps. In this respect I would

like to thank Robin Bertram, Mike Murphy, Tony Schmidt, Peter Smith, Alain

Stragier and Denis Vandervelde, all of whom have generously helped in this

endeavour.

This article has been taken from many sources, some of which are photocopies made from individual pages some time ago without my noting their origin. Individual references are not indicated within the text at their place of use, but some of those used or consulted include:

Arab Posts appearing in French in LOP. 25 of July, 1935 from a book published by the Egyptian Post Administration, for the, tenth Universal Postal Union Congress hold at Cairo, on 1st, Feb., 1934.

Le Barid Sus Beybars Et Mohamed Aly LOP 69 Jan 1950

The Post Office Under The Caliphs; LOP 97 April-July 1957 reprint from (The stamp collector’s Magazine, February 1867)

The Pigeons Postal Service; LOP 109.

Interpostals LOP 125 April 1972

Post Office Openings; LOP 113 April-July 1964; by Ibrahim K. Chaftar

The. Horse Post In The Kingdom Of The Mamalukes ; THLP 1959 Ismail H. Tewfik Okday

Postal History of Egypt to 1900, Samir Amin Fikry

Handbook of Holy Land Philately, Vol1 & Vol2, Anton Steichele

Byam’s Egypt 1961, Robson Lowe

Israel-Berichte Nr.19

Cornphila Stamp Auction April 2000

A Snapshot Of Egypt’s Postal History, The Egyptian Mail, December 3, 1994, Samir Raafat

The Egyptian Post Museum, Webb Site

Arabic News, Webb Site.

Ancient Inventions, Peter James and Nick Thorpe Ballantine Books

The Early History of Data Networks, Gerard J.Holzmann, Björn Pehrson

Medieval Warfare Source Book Vol2. - Long Distance Communications, David Nicolle

The Middle East, Bernard Lewis

Egypt Blue Guide, Peter Stocks

A World Atlas of Military History Vol.1 to 1500, Arthur Banks

The Penguin Atlas of Medieval History, Colin McEvedy

An Outline of the Egyptian & Palestine Campaigns 1914-1918, Maj.Gen. Bowmann - Manifold.