PRESENT: Eighteen members and one visitor attended. Apologies for absence were received from four members.

The Chairman opened the meeting by welcoming those present, regretted the absence through illness of John Sears, and wished all members, whether present or not, a Happy Christmas and contented and peaceful New Year.

The Secretary then mentioned the recent list of members published with the QC, and said that two more had requested their details to be made known. Notification was received from the ABPS that affiliation fees had risen from 60p to £1 per British member; there was discussion about the necessity to remain affiliated.

We have been invited by the Israel Philatelist magazine to provide three pages of information about the Circle for a special issue marking Israel 2008 in Tel Aviv next May; and to contribute an article on the basis of "What I collect" by The Stamp Magazine. It was agreed that we should make every attempt to provide such material - and yet another appeal was made for a Publicity Officer: the position has remained open for far too long, and its filling could bring enormous benefits to the Circle.

Edmund Hall spoke of reaction to his plan to use the website as a source of all information about Egyptian stamps and philately in general, and appealed for members to contribute material. This trail-blazing plan could work only with the co-operation of all, he said, while appreciating an understandable reluctance to reveal half-worked-up research. The meeting encouraged him to continue with his efforts, and asked all members to contribute to building a solid database of information.

Brian Sedgley said that the Auction account had provided further funds to the General account, but it was noted that there had been a decline in the number of members bidding in the recently-completed Auction 44. Officers appealed to members to place attractive material on offer, and then to bid for it!

The remainder of this report was contributed by John Davis (ESC 213):

The subject of this afternoon's talk and display was new to me in that I knew virtually nothing about the Rural Postal Service but Mike Murphy's display was helped by a handout entitled: Rural routes mentioned in the 20 Postal Bulletins held by the ESC 1889-1925.

Mike first thanked Tony Schmidt for generously providing access to Postal Guides 8 and 9, which include crucial itineraries of rural postmen's routes in detail, while the Postal Bulletins recently acquired by the Circle from Peter Feltus record several hundred rural routes or lines. Thanks also to the late Mohammed Shams el-Din who had, many years ago, sold some 100 covers to Mike at £1 each, a nominal price; this provided the basis for his collection; and last but not least, thanks to Ibrahim Shoukry, Peter Smith and Dennis Clarke for photocopies of their collections.

Rural lines were based within governorates and only rarely seem to cross governorate borders. The system was started on May 1, 1889, though the notice published in 1887 proposed a start date in 1888. It didn't happen. The full notice of the actual starting date was on April 25, 1889, with the initial list of routes published as an annexe which, unfortunately, we do not have.

When the government took over the postal administration from the Posta Europea in 1865 there had been only 19 post offices but by the start of the Rural Service the number had risen to 173 and the introduction of the new service doubled that number with the addition of 172 stations.

The basis of the service was simple: to provide a postal service without the expense of an office and staff. Within a village a Rural Post box for reception of letters was set into the wall of a building or nailed to a tree, and within the box was a handstamp in the form of a long oval, or cartouche, which bore the village name. Only the postman had the key to the box; only he had access to the cartouche stamp.

The first Service Rural marking was a circle with a date bar and the postman had to fill in the details by hand; only three are recorded on cover. A larger oval marking followed, again with a space for manuscript addition of date or village name. Mike showed copies of all 14 of these ovals that he has on record, dating between August 1889 and August 1894. The earliest in his collection is August 2, 1889, from Tunub.

Postmen were relieved of the burden of handwriting the dates when the two hand-stamps that have become familiar were developed: one circular, indicating the parent office, and the other the cartouche. Experimental usage of 213 cartouches on Type XI interpostals - known in at least four sets - must have been carried out between June and August 1890. In Egypt Gino Piperno obtained a set from relatives of Penasson the printer, and brought them to London 1960 for discussion. Dr William Byam and the experts decided that they probably were intended as another aid for the postman - to seal an envelope to contain letters from a particular Rural box: the experiment was not followed through. The Postal Museum in Cairo has 132 of these IPs on display, and recently a set of 213 (but including three duplicates) was sold on eBay.

In the earliest years there were three types of circular datestamp:

All of them carried numerals somewhere in the CDS, specific, it is thought, each to a Rural line depending on that parent office. The Rural Service markings can be set aside for the the moment since although their appearance was similar they were clearly of a different generation and none is recorded before 1909.

All of them carried numerals somewhere in the CDS, specific, it is thought, each to a Rural line depending on that parent office. The Rural Service markings can be set aside for the the moment since although their appearance was similar they were clearly of a different generation and none is recorded before 1909.

Mike has carried out an enormous amount of research into these numeral markings and has been able to prove, using maps and the records of cartouches used in conjunction with the numeral CDSs to back up the Postal Guide itineraries, that the theory is correct: for Zagazig, which has three numeral marks, Zagazig 1 is the Zagazig-Mit Abou Arabi line; Zagazig 2 is Zagazig-Karadis; and Zagazig 3 is Zagazig-Kafr Abou Nagah.

One area of interest was how villages of cartouche level early on in the scheme developed to become their own parent offices with their own lines, while others remained with cartouches.

Some Rural lines were circular, arriving back at the parent station, but most were linear, involving an overnight stay. Postmen were urged to stay only in designated locations, for security of the mail. As well as attending the boxes the postman would have mail to deliver, either collected from his parent office on his "outward" route, or delivered to him at his overnight point by courier for delivery next day: incoming mail receives no cartouche, since it has no connection with the postbox but is delivered by hand. When a recipient is not present, regulation required delivery to be attempted on three successive delivery rounds before return to the dead letter office.

The Rural postman travelled by donkey (if he could afford one), and just after the end of World War I the Post Office maintenance subsidy was increased from £E1 to £E2 a month. During the War all donkeys had been requisitioned by the military but so important were Rural Service donkeys that they were exempt.

Mike related his experiences excavating at Mit Rahina, ancient Memphis, when he spotted a young man on a bicycle going past day after day, and how he discovered that there was a Rural postbox set in a wall of their dig-house. The young man was a Rural postman based at nearby Bedrachein: the system had barely changed in 100 years - except that donkey had given way to bicycle!

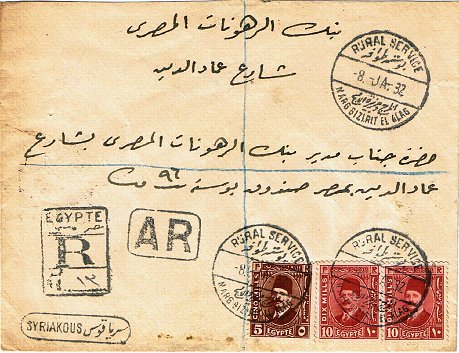

After a break to view the comprehensive array of material, Mike turned to ancillary services: as far as Avis de Reception (AR) mail is concerned it would appear that the postman carried the AR handstamp with him, but the question of AR cards and who carried them is not resolved. Certainly the service was used (see illustration above).

Postcards were also carried, and both Registered and Express postcards were shown. The meeting was amused at the thought of an Express letter starting its journey on a donkey! The Express rate was originally 20 millièmes inclusive of postage.

Initially the service was available for correspondence only, not including the carriage of money or parcels, but in 1896 parcels were accepted up to 1kg, for which the postman received 5 millièmes per parcel. The 1902 Bulletin indicated that from March 1 both ordinary and registered parcels would be carried up to 3kg.

As far as postage due items were concerned, members queried whether the rural postman collected the monies due? The service did not allow the carrying of money, but the postman himself did carry postage due stamps and presumably collected the revenue arising. Incoming postage due items are virtually unknown, but Mike showed one odd cover with an apparent deficiency of 18 millièmes (double the amount not paid) whereas the postman's arithmetic was somewhat over-zealous and the item was charged 36 millièmes. A note in French on the cover indicated that a senior postal official was not impressed!

Free franking of "official" mail was prevalent within the Rural Post (25 per cent of the 3,300 covers Mike has surveyed) and several items carried indications of how the postman recognised such mail. Government sealing labels (banded mail) were used as well as "Official ovals" and the mail went free of charge; both black on white labels and the much more attractive white on black labels were shown, as well as various cachets indicating official use. In one case the postman had applied a boxed T mark and had crossed it out when he realised that the mail should go free. All court correspondence went free as Official mail, but not lawyers' letters to clients.

Different inks on different postmarks on a cover raised the question as to where some handstamps were used; the postman himself carried an ink pad, Rural Service CDS and R-mark (and also AR?), so all of these - and the cartouche in the box - should have been struck in the same ink, but other marks were struck at the parent office.

Mike showed mail sent by the archaeologist John Garstang from Araba el Madfuna (ancient Abydos) to the Mena House Hotel. This item is very definitely in the wrong collection! A cover was shown with no fewer than 17 CDS markings, two of them Rurals, and a newspaper was sent registered at a cost of 1 millième for the postage and a further 10m for registration.

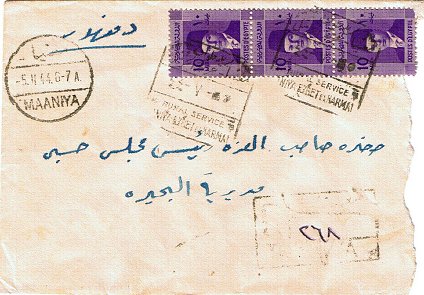

A square Rural Post cancel (illustrated above) was shown from the 1940s, when Boy King issues were in use, and the question arose as to when the system came to an end. It appears that it may still be alive and kicking and that the postal agencies introduced in the 1960s do not appear to be its death knell. In 1975 there were no fewer than 17,000 rural stations, and covers are so much sought after that a number of (happily obvious) forgeries were shown.

All in all, a wonderful display and we all came away much better informed. The Chairman thanked the speaker, announced himself "gobsmacked", and members showed their appreciation in time-honoured fashion.

" Mike has developed a comprehensive database of more than 750 Rural lines and their markings, and would welcome queries from members about markings difficult to make out; as well as photocopy or scanned examples of any Rural covers: email maalish (at) hotmail.com

|