| The Maritime Service of the Egyptian Posts | 637 | Handstamps of Private Shipping Lines | 645 |

| Paquebot Mail | 638 | Shore Facilities | 648 |

| Foreign Sea Post Offices in Egyptian Waters | 642 | References | 650 |

This chapter is concerned with mail that was posted on board ships sailing to or from Egypt, or at ship-side shore facilities. In the pre-philatelic period international mail was customarily entrusted to captains of ships for carriage to the port of address. Such letters are known from as early as the fourteenth century. However, they bore no handstamped markings, but only directions in manuscript (generally in Italian) with the name of the ship's captain. The first handstamped ship markings from Egypt were those of arrival at Toulon or Marseille during the Napoleonic occupation; they are treated in Chapter II. In this chapter are treated the Egyptian floating post office, mail received from ships (paquebot mail), private mail boat services, and foreign mail boat services.

It is necessary to begin with some words about the Egyptian steamship line that operated in the eastern Mediterranean and in the Red Seal. It was founded as the Medjidieh Company on February 1st 1857, flying the Turkish flag and primarily serving the Red Sea Ports. Ismail Pasha, on becoming Viceroy, authorized the formation of the Egyptian Company for Steam Navigation on May 4th 1863. It was nominally a private company, but the Viceroy had a personal financial interest in it and it was subject to much government supervision. It took over the six ships of the Medjidieh Company. On April 7th 1864 the Company was granted a monopoly for the passenger and freight traffic on the Nile and the Egyptian canals, and the Ottoman Sultan authorized it to adopt the name Azizieh Misri Company. Many new ships were soon acquired and they plied not only the inland waters, but the Mediterranean and Red Seas as well. A postal notice of May 3rd 1865 announced weekly sailings from Alexandria and from Suez; the former reached Constantinople in 3˝ days. The Red Sea service became less frequent, every ten days, about 1867. The Company showed persistent financial losses and in 1870 the Government took over full control and the name was changed to Administration des Paquebots Postes Khediviaux. Operations were interrupted in 1877 owing to the Russo-Turkish war, but were resumed in June 1878.

Losses continued, and eventually the Company was sold to British interests in 1898. From then it was operated under the name Khedivial Mail and Graving Dock Company. For convenience, the line is generally referred to as the Khedivial Mail Line (KML), regardless of the official name at the period being considered.

When Egyptian extra-territorial post offices were established at consulates in the Ottoman Empire in 1865, the mails were carried by the KML. At some later time, apparently 1875, post offices were installed on the ships for the purpose of receiving last-minute mails at the ports of call, handling the mail of passengers, and presumably for sorting in transit. The Postal Administration provided special date-stamps, inscribed UFFIZIO NATANTE ("floating office") (Fig. 1). In addition to the changeable date, a changeable slug reading either ALES. or COSP. was included to indicate the direction of sailing. The weight of the evidence, although not decisive, is that the indicium indicated the port of departure and ALES. meant northbound. However, the clerks did not seem to be diligent about changing the indicium when the ships reversed direction2, and examples even exist with the indicium omitted. One example is known in which the port indicium is replaced by a T and an unclear number (17 FEB 1878).

Fig. 1 The floating office date-stamp, SP.O-1

The date-stamp (Egypt Study Circle Type SP.O-1; the designation stands for Sea Post. Official) has been reported with dates from February 22nd 1875 to February 20th 1879 with ALES., and from November 10th 1875 to January 29th 1879 with COSP.; they are thus found only on the Third Issue. Examples are very scarce but not rare on loose stamps, but covers are rarities (I know of no more than five), whether the handstamp is a cancellation or a transit mark. Strikes with COSP. are distinctly scarcer than those with ALES. Although strikes are almost always on Egyptian stamps, an example has been reported on a Greek stamp, and others may exist.

Paquebot Mail

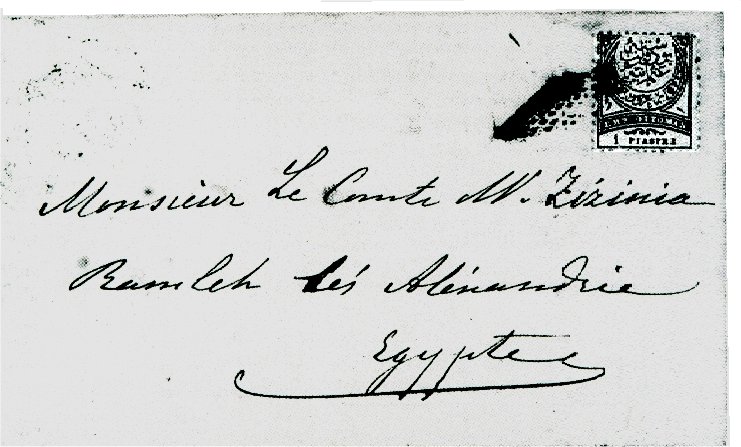

Letters posted on board ships, of various countries, arriving at Egyptian ports were commonly franked with stamps of the appropriate country: Turkish, Austrian Levant, Russian Levant, Greek, British, or French. If they were turned over to the Egyptian post office at the port of arrival, the custom was to cancel the stamps with the retta (Fig. 2), which, being dumb, did not give a false indication of the origin3. Letters turned over to one of the foreign consular offices were not cancelled with the retta, of course.

The UPU at its Congress in Vienna in 1891 developed the paquebot convention as a means of regularizing the treatment of mails originating aboard ships on the high seas (i.e., outside of territorial waters). French being the official language, the UPU used the term "pleine mer". The convention prescribed that letters franked with stamps of the country under whose flag the ship sailed, or of the country of the previous port of call, were to be accepted as validly prepaid if brought to the port post office by the purser of the ship, and were to be struck with an indication of this special category of mail.

Fig. 2 A letter received from a ship, with stamp cancelled with a retta

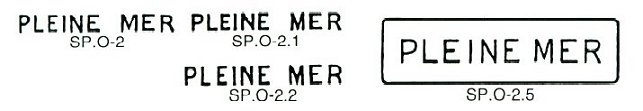

Egypt complied with the convention promptly and soon provided handstamps reading PLEINE MER to its major ports, Alexandria, Port Said, and Suez4 (Fig. 3). Each was slightly different:

| Port Said (seen 1893-99) | SP.O-2 (28.5x3.3mm, wide M) |

| Suez (seen 1893-99) | SP.O-2.1 (27.3x3.3mm, narrow M) |

| Alexandria (seen 1894-96?) | SP.O-2.2 (28.7x3.5mm, narrow M) |

| Alexandria (seen 1895-96?) | SP.O-2.5 (boxed, 44.5x11.5mm)

|

Fig. 3 Egyptian PLEINE MER handstamps.

These handstamps were customarily struck on the cover near the stamps, which were cancelled with the normal date-stamp of the port. (The measurements given are not exact, for differences in inking and impression are unavoidable.)

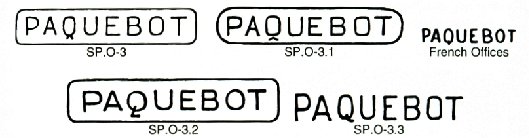

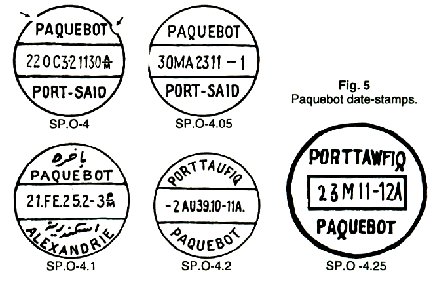

When the UPU settled on the use of the word "paquebot" or "packet boat", Egypt issued new handstamps5, which appear to have been introduced in 1899 (Fig. 4): SP.O-3 (46.5x9mm) for Alexandria (seen 1902-33), Port Said (seen 1899-1912), and Suez (seen 1902-05). At about the same time, Port Taufiq was added to the group. Conveniently located right at the southern end of the Suez Canal, it soon edged out Suez in importance, for the latter had a shallow harbor and was located northwest of the Canal entrance. To it was issued SP.O-3.1 (48x9mm) (seen 1901-1919). Port Said was also issued a second handstamp, SP.O-3.2 (54x11mm.), characterized by a distinctive letter Q (seen 1905-1919). Suez received SP.O-3.3 (42x7mm.), differing from the others in having no frame (seen 1905-1930). These paquebot handstamps were commonly used to cancel stamps, in contrast to the "pleine mer" types. Examples of all of them are fairly easily found on cover, whereas the plene mer types are quite scarce. The great majority are on covers franked with British stamps in the earlier years; later, they are most often seen on Egyptian stamps. The French post offices had their own handstamps in an omnibus type.

Hosking6 shows yet another type for Egypt, an unframed straight line with distinctive serifed letters. He properly expressed uncertainty about it; in fact, it is of Beirut (and can, of course, be found on Egyptian stamps).

Fig. 4 Paquebot handstamps.

By 1914, perhaps earlier, Port Said was given a circular date-stamp (Fig. 5) incorporating the word "paquebot". This was presumably intended to supersede the former type, but in fact, the two were used concurrently. Apparently two devices were provided, in one of which the collection time was expressed in four ciphers with A over M, or P over M following (reported 1914-62), and in the other, only two ciphers were used, followed by a dash and another numeral, without AM or PM (reported 1921-67). The first of these suffered damage early on, developing a break in the circle at upper left and a dent in it at upper right7. A new style of date-stamp, having the date enclosed in a rectangle and with European inscriptions only, is known used in the 1970s. Alexandria also received a circular paquebot date-stamp (reported 1925-68). Port Taufiq was at first given a small date-stamp, with spelling TAUFIQ (reported 1939-56), struck usually in black, but sometimes in dirty magenta. It was replaced in 1956 by a much larger device having the spelling TAWFIQ. Although the latest reported date is 1968, it may well be in use still (this also applies to Alexandria and Port Said). A curious handstamp inscribed BAGCE BOT in a rectangle, with space for a handwritten date, has been reported by Hosking6 used in 1983 at Port Taufiq.

The paquebot date-stamps of Port Said are quite common and those of Port Taufiq nearly as much so. That of Alexandria, however, is scarce. Alexandria slipped in importance as a port of call over the years, as more and more ships bypassed it in favor of Port Said. Suez became of so little importance as a port of call for large ships that it was apparently never issued a paquebot date-stamp.

There are three other significant Egyptian ports which in principle might have used a paquebot mark: Ismailia, Kosseir, and Mersa Matruh. The diligence of sea-post enthusiasts in contriving philatelic covers to be posted in minor ports by pursers of wandering freighters might possibly have met with success, and examples from these three ports (as well as Suez) may yet turn up.

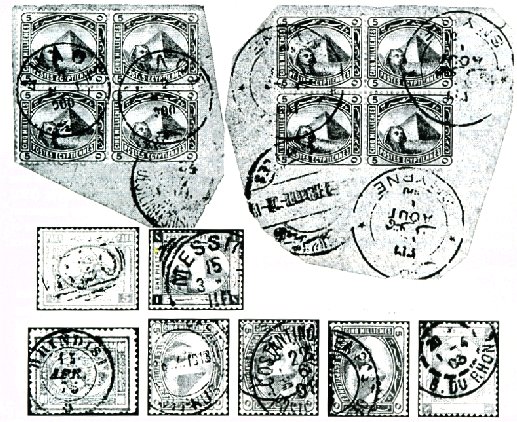

The foregoing discussion is concerned with mail arriving at an Egyptian port, but mail from ships leaving Egypt also received paquebot treatment at ports of arrival in foreign countries, especially Mediterranean ports. Accordingly, Egyptian stamps may be found cancelled with the paquebot handstamps of ports in England, France, Italy, Greece, Turkey Fig. 6 A selection of foreign arrival cancellations on Egyptian stamps.(including foreign offices therein), Lebanon, Syria, Palestine, Cyprus, Aden, and possibly other ports on the Red Sea and Indian Ocean. The appropriate markings have been cataloged by Hosking6. Before the UPU paquebot convention, and in some cases afterwards, the stamps were cancelled with the ordinary cancellation of the port; a selection is shown in Figure 6.

Fig. 6 A selection of foreign arrival cancellations on Egyptian stamps.

Foreign Sea Post Offices in Egyptian Waters

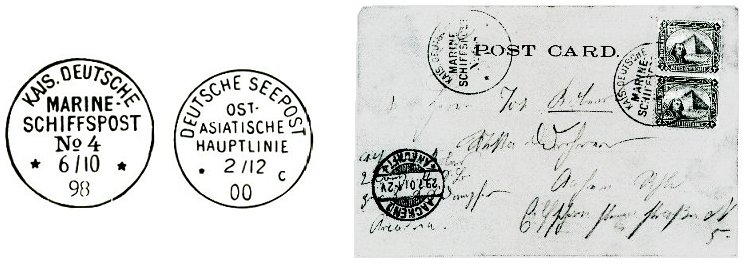

The ships of several foreign countries calling at Egyptian ports carried post office facilities on board. Those of the Austrian, French, and Italian steamship lines are described in Chapters VII, X, and IX, respectively. Although the British steamship lines did not carry the same sort of facilities, they did make use of movable letter boxes (Chapter VIII).Germany operated steamships through the Suez Canal to serve the Colonies in East Africa, the Far East, and the Pacific islands8. Most of the ships carried sea post offices, which used date-stamps inscribed DEUTSCHE SEEPOST plus identification of the line: OST-ASIATISCHE, OST-AFRIKANISCIIE, AUSTRALISCHE, BOMBAY, MITTELMEER9. To reach their destinations, most of these ships passed through the Suez Canal, and passengers and crew had opportunity to buy souvenirs and postcards in Port Said or Suez. The postcards were common]), formular cards, clearly proclaiming their Egyptian origin, which was in many cases confirmed by a message from the sender. Nearly all examples that I have seen are franked with German stamps, cancelled by the date-stamp of the Ost-Asiatische Hauptlinie, but as a rarity, Egyptian stamps were also used (Fig. 7). Examples from the other lines presumably exist.

German naval vessels also carried post offices on board in the period 1895-1914. Their date-stamps were inscribed KAIS. DEUTSCHE MARINE-SCHIFFSPOST and a number (Fig. 7). The moderate traffic through the Suez Canal increased greatly in 1900-01, owing to the Boxer Rebellion, and large numbers of troops had an opportunity to send mail home. Such mail was nearly always franked with German stamps, but Egyptian stamps were also used, albeit rarely (I have seen the 2m. and 3m. of the Fourth Issue).

Fig. 7 German naval and maritime date-stamps. A German navel post office postmark on a postcard

The Royal Romanian Steamship Line, which had a connection with Norddeutscher-Lloyd, carried a post office on board on the route Constanta-Alexandria, which may have begun in 1898 or earlier. Four types of cancellation are known from it. One is a double-circle device, inscribed simply CONSTANTA-ALEXANDRIA or vice versa. It was apparently in use up to 1914 or later and has been seen cancelling stamps of Egypt (1902 issue)11, Austrian Levant, French Levant, and Turkey, and must surely exist on Romanian stamps. The service was probably interrupted by World War 1, but afterwards, new types of date-stamps appeared, inscribed BIR. AMB. MARITIN / CONSTANTA-ALEX(S)ANDRIA or vice

versa (Fig. 8). They have been reported with dates from 1927 to 1938 and have been seen on stamps of Romania, Italy, France, Lebanon, and Egypt12. Examples of these date-stamps arc very scarce and the few covers that are known are largely (but not exclusively) philatelic.

Fig. 8 Date-stamps of the Romanian sea post office.

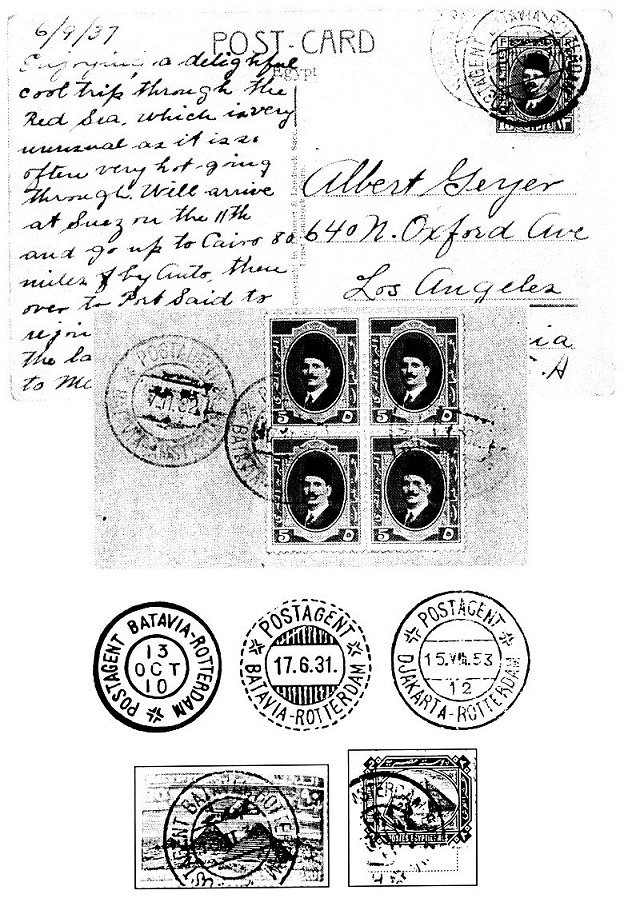

Sea post offices were carried on board Dutch ships plying the route to the Dutch East Indies by way of the Suez Canal13 The date-stamps, which read POST AGENT / A\ISTERDAM-BATAVIA, BATA VIA-ROTTERDAM14, or DJAKARTA- ROTTERDAM, (or vice versa) are known on Egyptian stamps from at least 1910 until 1936 (Fig. 9), and probably lasted until 1938. Cockrill15 states that there were five types of date-stamp for the first route and three for the second. I have seen but one cover (Batavia-Rotterdam, 11 VI 37), a large fragment (Batavia-Amsterdam, 7 11 32), and a small number of loose stamps.

Fig.9 A cover with Egyptian stamps cancelled at the Batavia-Rotterdam sea post office, a piece with Batavia-Amsterdam cancellation, and Dutch sea post office date-stamps.

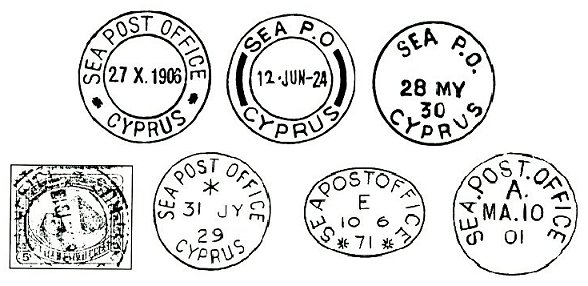

Cyprus maintained a sea post office on ships sailing between Cyprus and Egypt16. A contract was signed with the Limassol Steamship Company on October 15th 1906; it expired in 1912 when a new contract was signed with the Khedivial Mail Line. It was later allowed to lapse. However, a new contract came into effect on February 17th 1928 and lasted until 1932. The date-stamps used are shown in Figure 10; they can be found on Egyptian stamps. Although they are quite scarce, covers are known; most of them are philatelic. The primary purpose of these arrangements was to shorten the delivery time by sorting the mails en route; accepting letters posted on board or at shipside was secondary.

Fig. 10 Date-stamps of the Cypriot sea post office. Fig. 11 Handstamps of the Indian sea post office.

A sorting office of the Indian postal service was provided on P&O steamers carrying the mails between Suez and Bombay and beyondl7, apparently beginning in 1868; the service was fore shortened to Aden-Bombay in the 1880s and was terminated in 1914. Several variants of date-stamps reading SEA POST OFFICE, with a letter between the inscription and the date, were in use (Fig. 11). These handstamps are very common as backstamps on letters to and from India, but are quite scarce actually cancelling stamps. I have seen one example on an Egyptian stamp of the Fourth Issue.

Handstamps of Private Shipping Lines

The distinction between official and private sea post services can be made formally on the basis of who operates the service. In cases where a government post office was not maintained aboard, the ship's purser in principle carried out some mail functions and was usually provided with some sort of handstamp. Such handstamps identified the ship and the company operating it, but in general did not have date indicia.

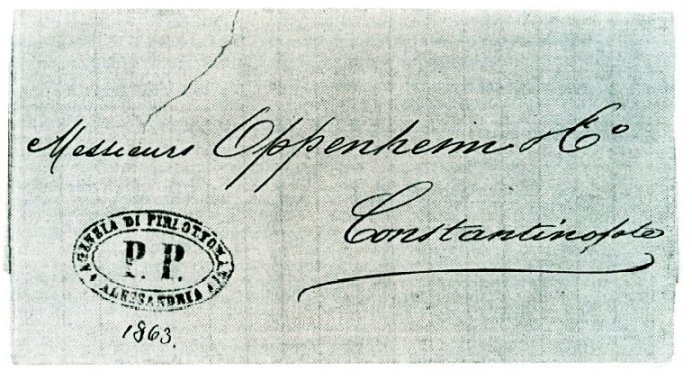

By far the earliest handstamp of a private shipping line is that of the PIROSCAFI OTTOMANI, an Italian-owned firm that for the most part served Constantinople and ports of the Aegean Seals. It had an apparently short-lived Agency at Alexandria. Stampless covers exist bearings its handstamp (Fig. 12) in 1863. I have encountered fewer than five examples.

Fig. 12 The handstamp of the Piroscafi Ottomani.

Less is known about a Russian shipping line, Aleksandrieskoe Parakhodnoye Agentsvo ("Alexandria Steamship Agency"), which is said19 to have issued an imperforate stamp in pale blue, denominated "25", in 1886.

In the twentieth century the handstamps of two shipping companies closely associated with Egypt can be found cancelling Egyptian stamps: the Khedivial Mail Line and the Societé Misr de Navigation Maritime.

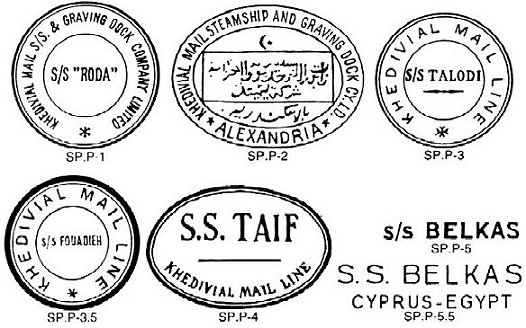

The ships of the Khedivial Mail line operating in the eastern Mediterranean and the Red Sea are known to have used five or more types of purser's handstamp to cancel stamps (Fig. 13) (there are additional handstamps found on covers, but so far not cancelling stamps). They have been given numbers beginning SP.P- (Sea Post. Private). I have seen SP.P-1 with the names of the ships RODA, BOULAC, and RASHID., SP.P-4 with the ship's name TAIF, SP.P-3 with the ship's name TALODI, and SP.P-5.5 with the name BELKAS, but other ships must also exist, such as KOSSEIR.

Fig.13 Handstamps used on KML ships.

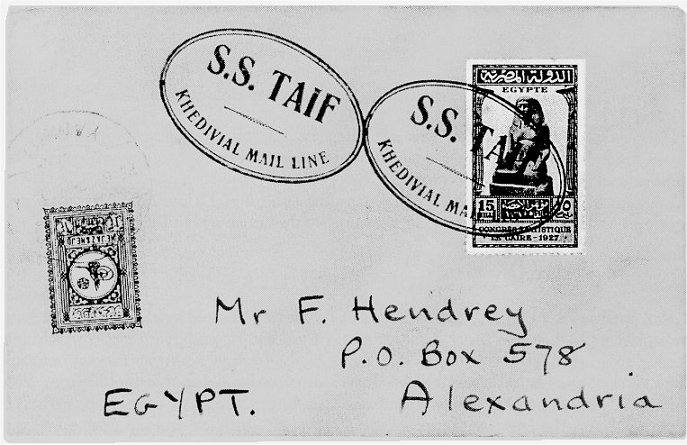

Most of the covers on the philatelic market are "Hendrey" covers, dated between 1928 and 1932. F. Hendrey20 was a dealer in Alexandria and most of the covers are addressed to him, generally at Barclays Bank or a post office box (Fig. 14); others are addressed to different persons, but in Hendrey's handwriting. Hendrey produced a large number of covers and they are consequently not difficult to find and should not command the high prices that some dealers ask. On the other hand, they all actually traveled and they were franked at the proper rate with contemporary stamps. At first, he used only Egyptian stamps, but he later became bolder, using the stamps of a variety of countries; I have even seen a Hendrey cover franked with stamps of Belgian Congo! Hendrey also arranged first-flight covers of the period.

Fig. 14 A typical Hendrey cover.

The Navigation a Vapeur "Panhellenique" had an agency at Alexandria. A cover is known from 1911, franked with a 5m. of the Fourth Issue, cancelled with a straight-line ΦEΣΣAΛIΛ in purple (presumably the ship's name).

The Navigation a Vapeur "Panhellenique" had an agency at Alexandria. A cover is known from 1911, franked with a 5m. of the Fourth Issue, cancelled with a straight-line ΦEΣΣAΛIΛ in purple (presumably the ship's name).

Less is known about the Societé Misr de Navigation Maritime, which used dated handstamps SP.S-I and SP.S-2, known with dates in the late 1930s (Fig. 15). They do not seem to belong in the "Private" category, for the date-stamps closely resemble those made for the Egyptian Postal Administration; accordingly, they are considered semi-official.

Fig. 15 Semiofficial date-stamps.

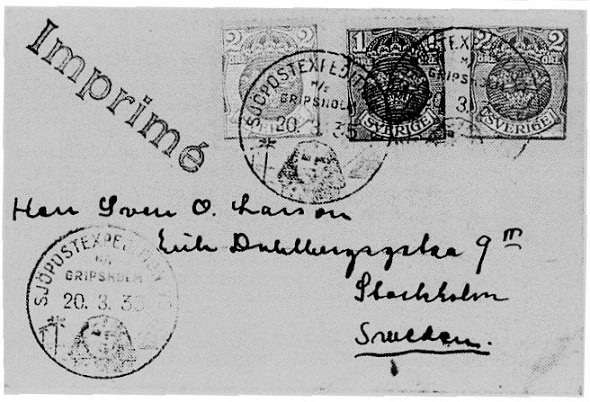

A charming pictorial postmark depicting the sphinx and a pyramid was used on a cruise by the M/F Gripsholm in 1935; presumably the cruise was to Egypt.

Fig. 15 cont. A cover with the M/F Gripsholm pictorial postmark.

Shore Facilities

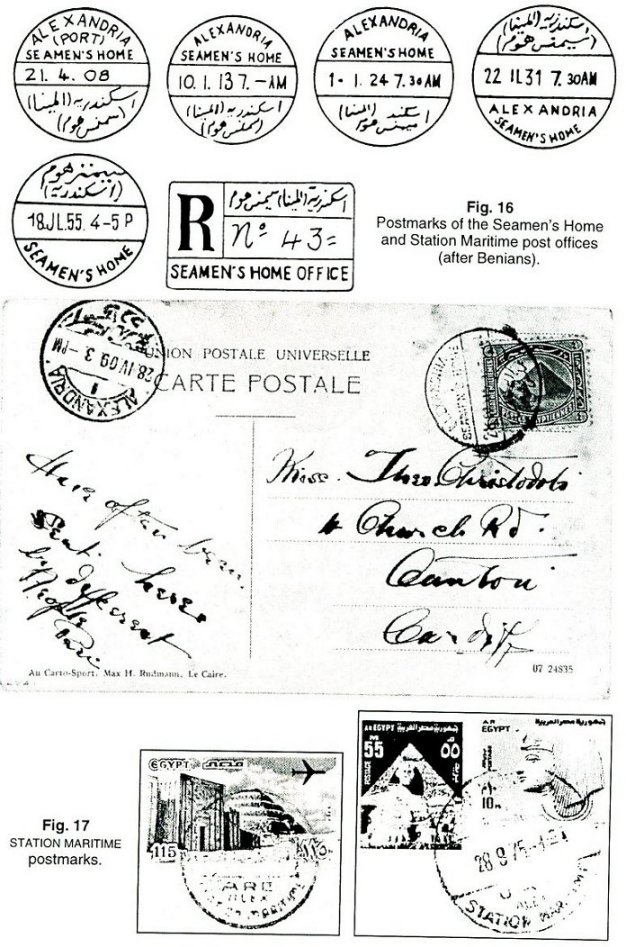

Postal facilities were provided at the docks in Alexandria, located inside the customs area, presumably so that personnel of ships could post letters (and receive them) without having to go through formalities21. The name of the facility, Seamen's Home, indicates the nature of the establishment, which provided recreational and worship facilities. Five different date-stamps (Fig. 16) have been recorded, but examples are scarce. The earliest is from 1908 and the latest so far recorded is from 1955. In later times, a post office was opened with the name Station Maritime (examples seen 1975-80); two date-stamps have been seen (Fig. 17), one in the UAR period, the other in the ARE period. The nature of covers posted there suggests that the function was different from the Seamen's Home and that it catered to passengers. Since the known dates of operation do not overlap, it could be a matter of change of name, along with function, but documentation is obviously needed.

There do not seem to have been similar facilities at other ports.

References

References

| 1. | C. Fox, QC VI (11), 133-6 (whole no. 71, Jan. 1973). |

| 2. | P.A.S. Smith, QC X11 (11/12), 233-5 (whole no. 139/140, Sep./Dec. 1986). |

| 3. | G. Boulad, L'OP No. 87, 445-51 (July 1954). |

| 4. | C.W. Minett, QC VI (6/7), 72-7 (whole no. 66/67, May 1966); J. Boulad d'Humieres, L'OP No. 123 (Apr./Oct.1970), pp. 366-81. |

| 5. | E. Drechsel, Paguebot Marks of Africa, Mediterranean Countries and their Islands, Robson Lowe Ltd., 1980; A.J. Revell, THAMEP I (8), 202-3 (Sep. 1957). |

| 6. | R. Hosking, Paquebot Cancellations of the World, self-published, Oxted, Surrey, 1977; Second Edition 1987. |

| 7. | L.. Alund, QC X1 (4), 137-8 (whole no. 121, March 1982). |

| 8. | E. Ey, Die Briefinarken der deutschen Postanstalten im Auslande and der deutschen Schutzgebiete, self-published, Augsburg, 1960, pp. 154, 171; A. Friedemann, Die Postwertzeicben and Entwertungen der Deutschen Postanstalten in der Sehutzgebieten and im Ausland, revised by 11. Wittmann, Vol. 3. Dr. Wittmann Verlag, Munich, 1969. |

| 9. | E. Drechsel, 1886-1986. A Century of German Ship Posts, Christie's Robson Lowe Ltd., 1987; P. Cockrill and A. Gottspenn, German Seapost Cancellations 1886-1939, Part 2, Philip Cockrill, London, 1987; E. Drechsel, Norddeutscher Lloyd, Bremen 1857-1970. History - Fleet - Ships - Mails, Vol. 1, Cordillera Publishing Co., Vancouver, Canada, 1994. |

| 10. | L. Alund, QC XI (6), 164-6 (whole no. 122, June 1982). |

| 11. | C.W. Minett, QC V1 (12), 145 (whole no. 72, Apr. 1969). |

| 12. | G. Boulad, L'OP No. 87, 445--51 (July 1954). |

| 13. | F.P. Traamberg and P. Cockrill, Netherlands Colonies, Maritime Markings and Ship Cancellations 1793-1939, Philip Cockrill, London, 1980. |

| 14. | R. Kreschel, QC XV (10), 275 (whole no. 173, June 1995). |

| 15. | P. Cockrill, Ocean Mails, self-published, London, 1939. p. 26. |

| 16. | W.T.F. Castle, Cyprus: Postal History and Postage Stamps, 2nd ed. Robson Lowe Ltd., London, 1971. pp. 196-7, 206; 3rd ed., 1987. pp. 156, 161, 167, 262. |

| 17. | J. Cooper, India Used Abroad, self-published, Bombay, 1950. pp. 97-100. |

| 18. | E.F. Hurt, and L.N. and M. Williams, Handbook of the Private Local Posts, F. Billig, New York, 1950. pp. 110-12. |

| 19. | Hurt and Williams, loc. cit. p. 18. |

| 20. | J. Sears, QC XV (3), 66-7 (whole no. 166, Sep. 1993) and XIV(8 ), 218-21 (whole no. 160, Dec. 1991). |

| 21. | F.W. Benians, QC X1 (5), 119-28 (whole no. 121, Mar. 1982). |

|

|