Since the defeat of French forces in Egypt in 1801 British politicians had tried, with marked lack of success to establish a government of the country that would satisfy both Turkish territorial claims on the area and the Mameluke Beys who were the de facto rulers.

Since the defeat of French forces in Egypt in 1801 British politicians had tried, with marked lack of success to establish a government of the country that would satisfy both Turkish territorial claims on the area and the Mameluke Beys who were the de facto rulers.

By 1803, the British via General John Stuart at Constantinople, finally managed to persuade the Mamelukes to take their forces from the Nile Delta into southern or Upper Egypt while awaiting efforts on their behalf in Constantinople. This would allow the remaining British troops in Egypt to finally embark for Malta. The British representative that General Stuart appointed in Cairo was his military secretary, Major Edward Missett. At this point Turkey suffered a number of mutinies within its provinces, including among its Albanian troops garrisoning Cairo and the Delta, which left the mutinies vying for control of Egypt with the Mamelukes.

Over the years, despite numerous appeals from Missett, that a military force should be sent to Egypt to secure British interests while anarchy reigned, nothing had been done; but it was now that the British Government decided to act, against strong French influence. Mohammed Ali, leader of the Albanians, was strongly entrenched and at the news that Major General Fraser's military mission had set sail Missett took the opportunity to inform the Mamelukes that the British forces would restore control of Egypt to them.

The small British force that finally left Sicily on March 6 consisted of the Light Dragoons, several battalions of Regiment of Foot, De Roll's Regiment (Swiss in British service), and Les Chasseurs Britannique (French and others in British service). This was further augmented by attached Sicilian Volunteers.

After a fraught journey Alexandria fell to the British on March 20. Missett now informed Fraser, falsely, that Alexandria was on the point of running out of food and explained that the town depended on the land around Rosetta for cereals and around Rahmanieh for cattle. This was probably in order to support the commitment he had made to help the Mamelukes on Britain's behalf, despite the fact he had no remit to do so. Fraser was now in a particularly difficult position: he had been ordered by his masters in London only to capture Alexandria. To strengthen his argument, Missett informed Fraser that the defences of Rosetta were in a dilapidated state and Mohammed Ali's Albanians were a mere rabble.

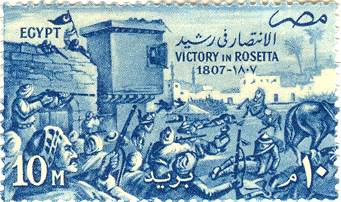

Fraser dispatched a small force of some 1,600 men under General Meade with two six-pounders to capture Rosetta. On March 31, 1807, the British troops arrived and, worn out by the long march, they entered the city, which appeared completely empty. The Governor of Rosetta (Rasheed), Ali Bey Al Salanklli, had however prepared a plan and asked the inhabitants of the city to help the 600 Egyptian (Albanians?) troops to prepare an ambush. As the British walked though the deserted streets they heard a call to prayers from the Zaghloul mosque, "Allahu Akbar" - it was the signal for an attack. Every house in the city was a fortress from which a barrage of fire rained down on the British troops, inflicting many casualties.

Further attempts were made to capture Rosetta, but to no avail. By September 19 the British army had been evacuated and slightly more friendly terms achieved with Mohammed Ali. As for the Mamelukes, who had failed to produce any help at all, they were embroiled in their own internal fighting during which several of their leaders were killed. In 1811 Mohammed Ali finally rid himself of these once formidable soldiers by ordering a great massacre at Cairo Citadel.

The Battle of Rosetta has inspired numerous writers, such as the novelist Ali Al Garim, who wrote his famous The Beauty of Rasheed. Also the late President Gamal Abdel Nasser used this battle as the beginning of his novel, For the Sake of Liberty.

On the last ESC visit to Egypt some members visited the Citadel, where, in the military museum, a picture of this battle was displayed. In front of it parties of schoolchildren with rapt attention had the story told to them by their teachers. One could not help wondering how many British schoolchildren could give any account of this piece of our common history.